The Bank of Ghana (BoG) commenced its policy rate hike cycle in November 2021 well ahead of major central banks such as the US Federal Reserve. US inflation in recent months has peaked and started declining while inflation in Ghana shows no signs of sustained disinflation. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) in its December 2022 consumer price index (CPI) and Inflation press release reported a year-on-year inflation rate for December 2022 as 54.1%. At 54.1%, CPI inflation is well above the inflation target range of 6-10% set by the Bank of Ghana though the policy rate is at its highest level in two decades. This suggest that the monetary policy of the BoG has largely not achieved its desired effect of controlling inflation. We argue that monetary policy effectiveness has been hampered by the monetary authority’s lending of over GHS40 billion to the fiscal authority financed by the creation of reserve money.

Price stability is essential for macroeconomic stability, and it is a bedrock for the Ghanaian economy. Getting inflation low and stable is crucial for the long-term economic wellbeing of every Ghanaian. Price stability is the responsibility of the Bank of Ghana. As stated under section 3 of the Bank of Ghana Act 2022 (Act 612), the primary objective of the Bank of Ghana is to maintain stability in the general level of prices. Since November 2021, the Bank of Ghana has increased the policy rate by an aggregate of 14.5%, which is more than twice the October 2021 value of the key interest rate. At 28%, the policy rate is at its highest level in more than two decades. However, the inflation rate is not showing sustained signs of slowing down. Inflation within that period has increased from 13.5% (October 2021) to 54.1% (December 2022). Admitted that it takes time for the full effects of monetary policy to be transmitted into the real economy, but the current interest rate hike cycle has lasted more than long enough to produce the expected signs of sustained disinflation. Most economists estimate an average of 12 months for monetary policy to have a full effect on an economy.

Why has the interest rate hikes not yielded a significant effect on price stability in Ghana? To answer this question, we will first explain how an increase in interest rate is expected to affect the economy and later show evidence of a simultaneous contrary policy which offsets the expected effect of the interest rate hikes.

Contractionary monetary policy (led by an increase in the policy rate) is the appropriate tool to fight inflation. In that regard, we agree with the Bank of Ghana in its effort to slow down inflation by increasing the policy rate. We are even of the opinion that monetary policy in Ghana is not restrictive enough to quickly return inflation to target. An increase in the policy rate reduces inflation by slowing down aggregate demand to give supply time to catch up in dealing with excess demand, which is the main cause of inflation. In addition, an increase in the policy rate helps to anchor inflation expectations around the target.

Monetary policy works mainly through financial markets. Central banks often adjust the supply of central bank money (supply of reserve balances) to keep the monetary policy rate – the interest rate at which commercial banks borrow from the central bank – around the set target. As a result, whenever inflation is above target, the central bank would announce a higher policy rate and instruct its traders to sell financial assets in attempt to reduce the supply of reserves. For a higher policy rate to achieve the expected impact on the economy it must be accompanied by a reduction in the supply of reserve balances. Unfortunately, in the case of Ghana, reserve money has been increasing at an astronomical pace at a time the central bank is supposed to be fighting inflation. A larger fraction of the increase in reserve money was used to finance fiscal spending. According to the 2023 budget statement 94% of the GHS44.5 billion fiscal deficit in 2022 was financed by the Bank of Ghana.

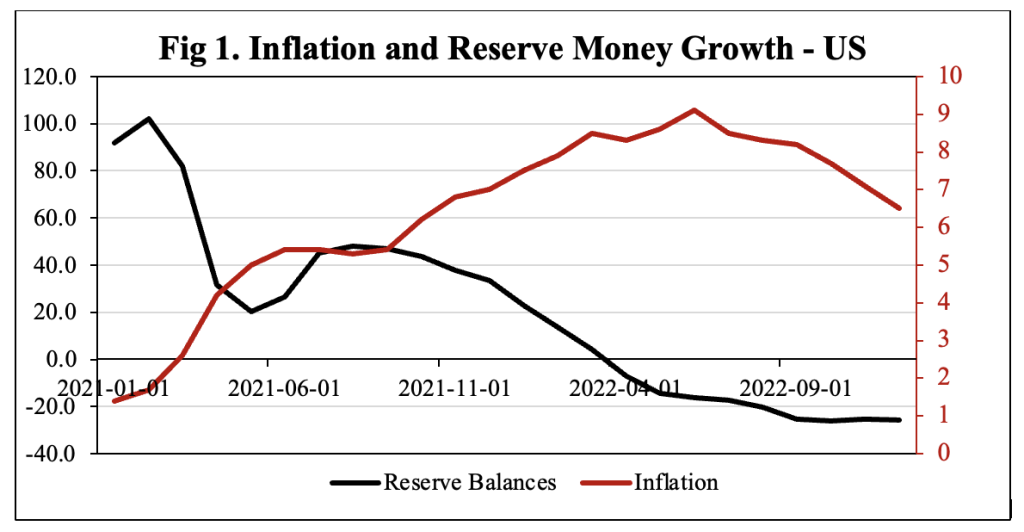

Sources: Constructed by Authors with data from Fred and BLS.

Note: There is a negative correlation between inflation rate and reserve money growth rate in the US from Jan 2021 to Dec 2022.

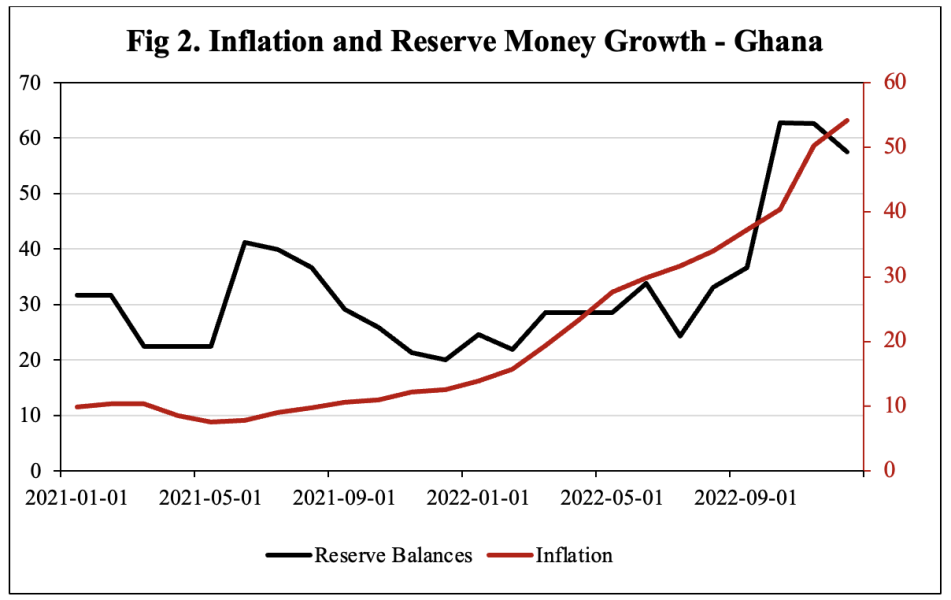

Source: Constructed by Authors with data from BoG

Note: There is a positive correlation between inflation rate and reserve money growth rate in Ghana from Jan 2021 to Dec 2022. Whereas the growth rate in reserve money has been declining in the US to complement the increase in policy rate, the growth rate in reserve money has been increasing to offset the impact of the increase in the policy rate in Ghana.

Almost all central banks around the world have been dealing with rising inflationary pressures since 2021. Just like Ghana, inflation in the US has risen above the inflation target of 2%. The Federal Reserve appropriately has responded by raising its policy rate by an aggregate of 4.25%. At 4.25%, the policy rate in the US is at its highest level since 2007, before the global financial crisis. In Fig 1, we show the relationship between the reserve money growth and inflation in the US. We can observe that the raising of the policy rate in the US is already beginning to have a significant effect on the inflation rate. US inflation (red line in Fig 1), in recent months has peaked and started to decline. It is worth noting that the Bank of Ghana started raising interest rates before the Federal Reserve and according estimates by economists, inflation in the US is expected to be stickier than that in Ghana. Consequently, one would expect that, if the Bank of Ghana began an interest rate hike cycle before the Federal Reserve, signs of disinflation should first be observed in Ghana and later in the US.

However, Fig 2 which shows the relationship between reserve money growth and inflation in Ghana indicates that inflation in Ghana is showing no signs of slowing down. If both US and Ghana are facing inflationary pressures and both central banks have increased their policy rates, why is there a difference in the impact on inflation? The answer to this paradox is observed in the behaviour of the growth rate in reserve money (the black lines in both figures). Whereas the growth rate in reserve money has been declining in the US to complement the increase in policy rate, the growth rate in reserve money has been increasing to offset the impact of the increase in the policy rate in Ghana.

By showing the above figures, we are in no way comparing the structure of the two countries. Developing economy central banks like the Bank of Ghana face different policy trade-offs compared to those faced by an advanced economy central bank like the Federal Reserve. The Fed is fortunate to face what most economists refer to as the “divine coincidence” – a term originally coined by two renowned economists, Olivier Blanchard and Jordi Gali, to describe a situation where stabilizing inflation at the target also implies reaching the optimal level of economic activity. The Bank of Ghana on the other hand, at least in the short run, must sacrifice optimal level of economic activity to achieve price stability. This makes achieving price stability a much difficult task for the Bank of Ghana. In a press release dated 9th February 2023, the Bank of Ghana explained the circumstances which led to the use of reserve money to finance fiscal spending – Ghana had lost access to the International Capital Market, domestic revenue was significantly underperforming and not realized, pushing government finances into near external and domestic default.

We can fully appreciate the circumstances which have led the central bank to increase reserve money to finance fiscal spending. However, we strongly believe that is not the optimal use of central bank resources. An inflation targeting central bank whose major objective is to maintain price stability should always ensure their actions do not jeopardize price stability. Monetary policy has its greatest impact principally in the long run—and primarily on the price level only. Using monetary policy to finance fiscal spending is not only unsustainable but incurs a greater cost to the economy compared to the short-term benefit of fiscal relief. It is therefore important that the central bank and finance ministry commit to zero fiscal financing in 2023 and beyond.

Written by

Dennis Nsafoah

Assistant Professor of Economics

Niagara University, NY

Member of Research Committee, Tesah Capital

Elikplimi Komla Agbloyor

Associate Professor, Department of Finance, University of Ghana Business School.

Chair of Research Committee, Tesah Capital

Data Scientist (Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence Applications in Business)