This is an academic article. The authors are solely responsible for the content of this publication. It does not reflect the views of Tesah Capital or any institution with which the authors are affiliated. We are grateful to Tesah Capital for providing a publication outlet.

Introduction

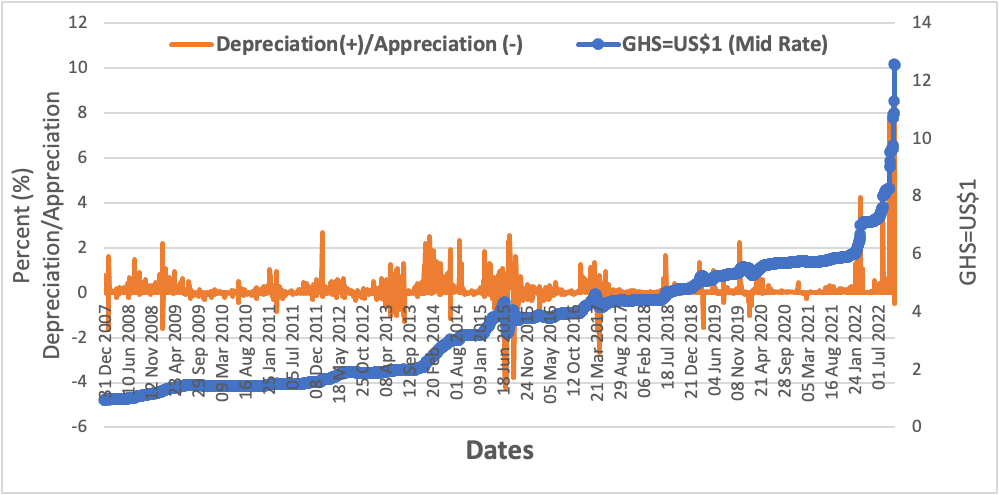

The Ghana cedi has depreciated markedly this year against the major currencies such as the dollar (year-to-date depreciation of 52.0%), pound (year-to-date depreciation of 42.3%) and Euro (year-to-date depreciation of 45.0%). The depreciation this year is quite unusual (see Figure 1) when compared to the year 2021 when the cedi depreciated against the dollar and pound by 4.1% and 3.8% respectively but appreciated against the Euro by 3.5%. The significant fall in the cedi so far this year (October 22nd, 2022) has been the highest in over 22 years. Indeed, by the end of December 2007 the cedi exchange rate against US$1 was GHS0.96 and this has since depreciated to GHS12.53 equivalent to $1 (as at October 22, 2022).

Figure 1: Historical Value and Movements in the Exchange Rate of the Cedi Against the Dollar (December 2007 to October 2022)

Source: Bank of Ghana (2022)-Accessed October 24th 2022

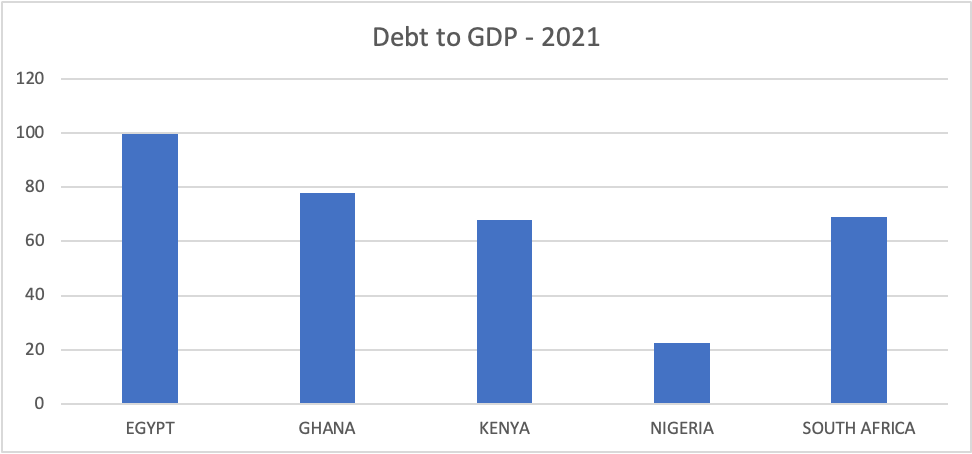

Aside the usual structural bottlenecks of being an import-dependent economy that exports mainly primary products since independence, the current depreciation being experienced has been driven mainly by both domestic and external factors. On the domestic front two main factors are responsible for the poor performance of the cedi. The unsustainable debt stock (see figure 2) and high debt service costs recorded at the end of 2021 raised concerns on the international capital markets about Ghana’s ability to service its debts and this had adverse implications for Ghana’s access to resources from the International Capital Markets (ICM). This meant that Ghana could not borrow from the Eurobond market, which has been a major source of reserve buildup for the central bank in the previous years. Secondly, the failure of the government to assure investors of pursuing a credible fiscal consolidation as indicated in the 2022 budget (instigated by low revenue mobilization and rising government expenditure) and increasing risk of default on debt service obligations, resulted in a downgrade of the country’s credit rating by Moody’s, Fitch and S&P. This sparked sudden reversal of capital flows by non-resident holders of Ghana’s domestic bonds whereas resident debts holders moved away from cedi denominated debt assets into holding forex. There is no doubt that one of the reasons why Ghana’s debt had increased substantially was the fiscal spending that was carried out in 2020 to contain and mitigate the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and its lingering impact in 2021, that led to a fiscal deficit of 11.4% and 9.2% of GDP in 2020 and 2021 respectively. The fiscal deficit in 2020 was also heightened by the political business cycle of excessive public spending especially in election years.

These domestic factors were putting severe unusual pressure on the cedi leading to the sharp depreciations. As the cedi depreciated the self-fulfilling prophesy kicked in and that caused further depreciation as importers and other speculators cashed in and increased their demand for dollars, pushing its decline further.

Figure 2: Ghana’s Debt to GDP Ratio Compared to Other Countries

Source: Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

With regards to the external factors, the lingering effect of the covid pandemic had resulted in global supply-chain bottlenecks and increased shipping costs that was transmitting into higher global inflation. As countries began to tackle the higher inflation, the Ukraine-Russia war commenced and immediately impacted on global oil prices, further increasing global inflation and its adverse consequences for import dependent economies such as Ghana and other emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs). The implication of the global price increases meant that by importing the same volume of goods (such as refined oil, Ghana needed more foreign currency and this further put pressure on the cedi causing it to depreciate and thus resulting in imported inflation.

With the global economy currently facing unprecedented levels of inflation, central banks around the world, principally the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, have sought to hike their policy rates to combat unprecedented inflation rates not seen in the last four decades. Successive rate hikes in the US have made the US dollar relatively stronger against peer currencies, appreciating by 14.11 percent and 17.92 percent against the Euro and British Pound respectively from beginning of year to October 25, 2022. Indeed, the dollar has strengthened by about 16% against a basket of currencies monitored by the Economist. Consequently, investors globally have diversified and transferred their assets into dollar denominated assets to hedge against inflation. The strengthening of the dollar on the back of hikes in Fed rates has also worsened the plight of the Ghanaian economy as non-resident investors repatriate and in some instances redeem their investments prematurely causing significant loss in reserves and depreciation of the Cedi.

Can the Cedi be pegged (fixed) against the dollar or should Ghana opt for a Currency Board?

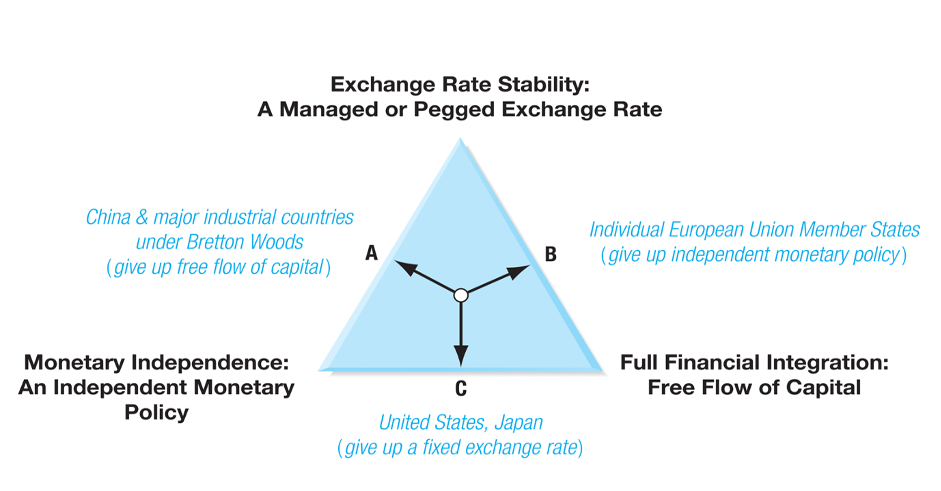

Some journalists, politicians and commentators have asked if the currency cannot be fixed or pegged for example against the US dollar. Further, Prof. Steve H. Hanke, a Professor of Applied Economics from the Johns Hopkins University has recommended that the nation adopts a Currency Board system. There are pros and cons of adopting a fixed exchange rate system or a Currency Board which is a hard exchange rate peg. First of all, adopting a fixed exchange rate system means we have to either give up free capital flows or independent monetary policy. This is borne out of the international macroeconomic literature known as the impossible trinity or policy trilemma where countries cannot have fixed exchange rates, free capital flows and independent monetary policy at the same time. Countries will have to choose two out of these three options.

Figure 3: The Impossible Trinity

Source: Eiteman, Stonehill, and Moffett (2021)

At present, Ghana has independent monetary policy and free capital flows, which imply that we cannot fix exchange rates (see Point C in Figure 3).

If Ghana decides to fix its exchange rate for example against the dollar and maintain independent monetary policy, then we would have to restrict capital flows. That is, we cannot allow foreign investors to invest freely in the economy or take out money freely out of the economy. This is because free inflow and outflows of foreign capital will mean the peg cannot be maintained. For example, investments into the economy will lead to an increase in the supply of dollars and a consequential appreciation of the cedi (breaking the peg). Further, an exit of investors out of the economy will lead to an increase in the demand for dollars and a consequential depreciation of the cedi (breaking the peg).

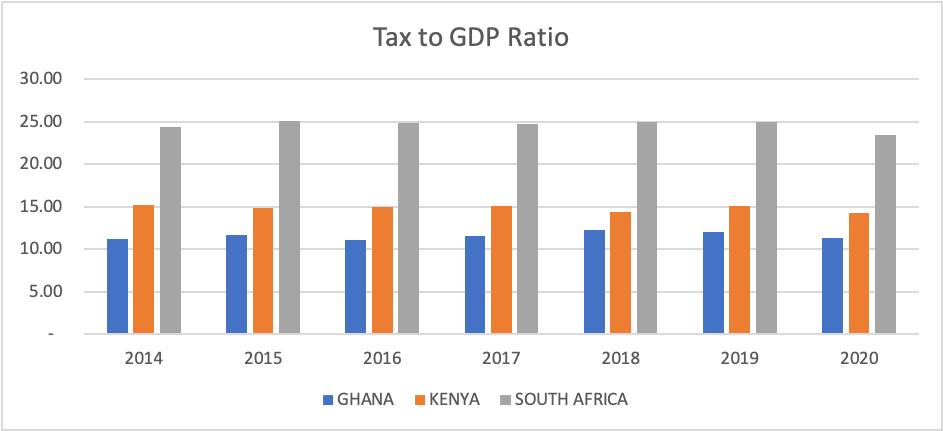

Ideally, maintaining a fixed exchange rate would have been a great way to have some stability in the cedi if we were able to raise sufficient domestic revenues to finance public expenditure and investment. In such a scenario, we would not need to rely heavily on foreign capital flows to fund the investment deficit and consequently it would be feasible to regulate capital flows to a certain extent. Unfortunately, Ghana has been unable to raise enough revenue over the years to finance its activities. Historically, the country has had low tax revenues as a percentage of GDP compared to similar countries (see Figure 4). Countries like China (see Point A in Figure 3) have been able to sustain a fixed exchange rate because of the huge efforts they put into domestic resource mobilization.

Figure 4: Tax to GDP Ratio

Source: Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

The suggestion that we should adopt a fixed exchange rate is an experiment that Ghana has embarked on previously. Indeed, we have had fixed exchange rates at various points in our history. Between 1957 and 1966, the cedi was pegged to the British Pound whilst between 1967 and 1982, the Cedi was pegged against the US Dollar amidst an independent monetary policy and restricted capital flows. However, this led to an overvaluation of our currency, leading to lower export proceeds and balance of payment issues. Apart from having low export proceeds, Ghana was also not able to raise enough revenue to finance its expenditure.

The second option for Ghana if we were to go for a fixed exchange rate is to allow free capital flows but sacrifice monetary policy (see Point B in Figure 3). Giving up control of monetary policy generally has some disadvantages. First, it means that we would not be able to use monetary policy to compensate for fiscal slippages which successive governments have mostly been guilty of especially in election years. This will be disastrous for the Ghanaian economy as politicians always think about the short-term benefits (political economy) they will receive from the policies they implement which may not necessarily be beneficial to the nation in the longer term. Under this option (fixed exchange rate and free capital flows), one possibility is to institute a Currency Board. The installation of a Currency Board helped to eliminate hyper-inflation in Argentina in the 1990s, but this could not be sustained. Thus, a Currency Board could reduce inflation, reduce interest rates, and promote exchange rate stability by restricting the ability of the central bank to print money without having the foreign exchange reserves to back it. The most popular example of a currency board is in Hong Kong.

A Currency Board means for every cedi issued, we should have hard currency such as the dollar backing it. The Currency Board adopts an accommodation policy. If for example, interest rates in the US increase relative to Ghana or a trade deficit occurs in Ghana, it means economic agents would change their cedis into dollars causing the dollar to appreciate and the cedi to depreciate. To avoid this, the Currency Board will buy cedis (to prevent a cedi depreciation) and sell dollars (to reduce the price of the dollar). The purchase of cedis will lead to a monetary contraction, leading to an increase in domestic interest rates that match the increase in foreign interest rates. Further, the monetary contraction should lead to a fall in prices and wages. The fall in prices and wages should make exports cheaper and more competitive theoretically leading to a correction of the balance of payments deficit. However, workers and producers are usually hesitant to accept a reduction in their wages or prices.

On the other hand, a reduction in interest rates in the US relative to Ghana or a trade surplus would lead to an inflow of dollars into Ghana. This will put pressure on the Cedi to appreciate against the dollar. To prevent an appreciation, the authorities will sell the cedi (reducing its price) and buy the dollar (increasing its price). Selling the Cedi would lead to an increase in the supply of cedis leading to a reduction in domestic interest rates corresponding to the reduction in the foreign interest rates. Further, the sale of the cedi would lead to a monetary expansion leading to an increase in prices and wages. The increase in prices and wages should make exports less competitive leading to a reduction of the trade surplus.

Instituting a Currency Board has some disadvantages. It would lead to a loss of control over monetary policy. The central bank would lose its ability to function as a lender of last resort to the banking sector as it cannot issue new currency if it does not have foreign reserves to back it. Without a lender of last resort, the Central Bank cannot intervene to restore financial stability in the event of financial crises. We know that financial and economic crises have become more frequent and severe. In addition, if we install a Currency Board, then the local authorities cannot use interest rates to guide or stimulate the economy. Further, a Currency Board requires strong institutions to make it successful. This is so because for example the central banking law has to be changed, the central bank will have to be restructured – for example banking supervision may have to be ceded to an independent body, parliament would have to debate and accept this proposal, the relationship between government and the central bank has to be strictly defined with the central bank unable to monetize government debt etc. At present, we don’t have strong institutions to ensure a currency board operates successfully.

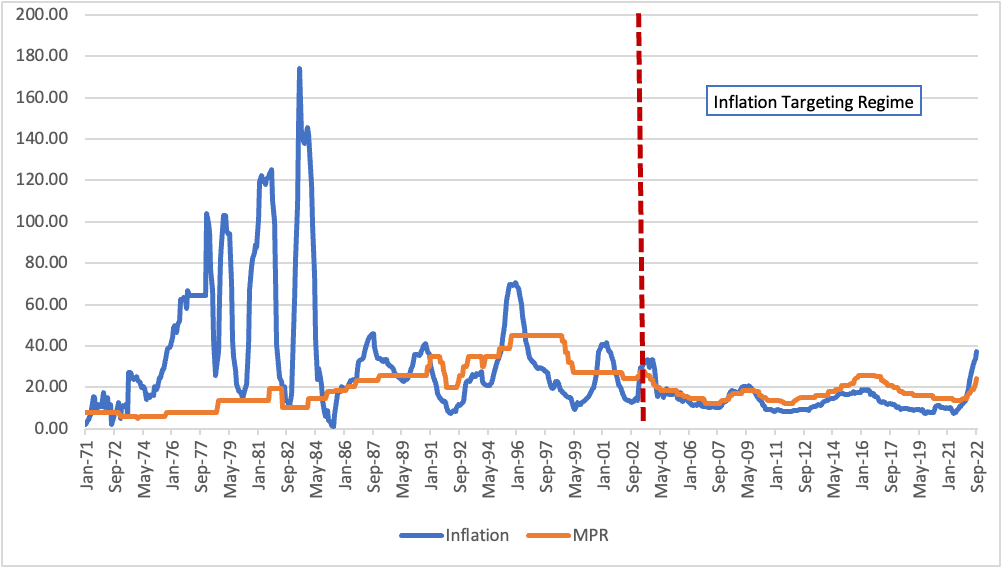

The present independent monetary policy regime of inflation targeting by the Bank of Ghana has to a large extent been successful in lowering inflation and stabilizing the cedi compared to the controlled and monetary targeting regimes that preceded inflation targeting. Before the current events, the Bank of Ghana had successfully steered inflation within its target band of 8+/-2% and had been credited with toning down inflationary expectations over the years since Ghana started inflation targeting (see figure 5).

The current unprecedented wave of global inflation (highest in over four decades for some countries) will require consistency in monetary policy direction and effective coordination of economic policies to reduce inflation while minimizing the adverse effect on growth providing time for the long-term structural issues in the economy to be dealt with to stabilize the cedi. Obviously, a pegged rate or currency board isn’t a feasible solution in the Ghanaian case. Ghana doesn’t have the luxury of foreign reserves to “fuel the engine of” a currency board or maintain a fixed exchange rate, especially when the fiscal authorities have shown consistent indiscipline in running a tight budget or low fiscal deficits.

Figure 5: Monetary Policy Regimes, Policy Rate and Inflation Rate, 1971-2022

Source: Bank of Ghana (2022)-Accessed October 24th 2022

In conclusion, while Ghana seems to be struggling to maintain macroeconomic stability especially with regards to the stability of the cedi, we do not think that a Currency Board is appropriate for Ghana. What Ghana needs is to build enough resilience to withstand external shocks such as commodity price shocks, global pandemics, global inflation and other unforeseen events. This requires both short-term and medium- to long-term measures. Certainly, a currency board and/or a fixed exchange rate isn’t the solution.

What then Should We Do?

Short-Term Measures

The fiscal and monetary authorities should communicate clearly and explain the current situation to Ghanaians to reduce uncertainty in the business environment and break the speculative and panic rush for dollars.

Apart from the IMF loan and the expected inflows of the cocoa syndicated loans, Ghana should seek the assistance of bilateral partners to obtain grants or loans to shore up our foreign currency reserves. This would help the Central Bank increase forex liquidity through increased market support and forward forex auctions to banks and BDCs which could potentially slow down or reverse the depreciation of the cedi.

The Bank of Ghana should also continue its gold purchase programme and discussions with the oil companies to boost its reserves way above the minimum threshold for months of import cover. We think that a target minimum import cover ratio of between 8-12 months would be ideal. For example, India had an import cover ratio of about 8 months and reserves in excess of $500 billion in August 2022. Brazil had an import cover ratio of 12 months and reserves in excess of $300 billion in August 2022. This accounts for why these currencies have not depreciated that much against the dollar amidst the global headwinds.

Medium- to Long-Term Measures

We need to restructure the nature of the economy from being highly import dependent and an exporter of raw materials. This can be done by;

- adding value to primary exports for import substitution and export promotion. This can be achieved through a well-designed and implemented import substitution industrialisation strategy such as the 1D1F programme.

- introducing policies to promote consumption of made in Ghana goods and services.

- introducing policies to discourage the importation of non-essential goods

- promoting the export of services such as education and health.

On fiscal policy, we need to;

- re-examine the Public Debt Management Strategy by borrowing less from international capital markets as it exposes the economy to ‘Original Sin’. In our view, external debt should form a maximum of 20-25% of total debt, while we reduce the participation of non-resident investors in our domestic debt market. This will enable Ghana to manage the disorderly exit of foreign investors and reduce substantially the pressure on the cedi.

- reduce the rigidities in our public expenditure by weaning many public institutions off the public sector wage bill, clean the public sector payroll of ghost names, re-examine the public procurement act to ensure value for money procurements and reduce the size of government and/or the parliamentary system

- prioritize social interventions and move away from indiscriminate subsidies to well-targeted pro-poor subsidies.

- Increase domestic resource mobilization with regards to widening the tax net to include the untaxed informal sector through the successful digitalization that has so far been achieved. In addition, we should pursue aggressively the collection of realistic property rates using digital platforms to minimize revenue leakages.

- Tackle corruption which has drained public funds and severely constrained the fiscal space.

- Ghana will need to have a second look at how political parties are financed. A lot of corruption is fueled by the award of contracts to party members and individuals and businesses who funded the political parties to win power.

- Ghana should strengthen the institutional agencies that have been set up under our constitutional rule against the misuse of public funds. This can be achieved if the checks and balances against embezzlement and corruption are strengthened and made functionally effective. Punitive sanctions should be legally applied to culprits so as to make corruption unattractive.

- strictly enforce compliance with BOG financing of Government not exceeding 5% of previous year’s revenue as stipulated in the Bank of Ghana Acts (612 and 918).

References

Eiteman, D.K., Stonehill, A.I., and Moffett, M.H. (2021). Multinational Business Finance. Pearson.

Contributors

Elikplimi Komla Agbloyor

Associate Professor, Department of Finance, University of Ghana Business School.

Agyapomaa Gyeke-Dako

Senior Lecturer in Economics, Department of Finance, University of Ghana Business School.

Ebo Turkson

Associate Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, University of Ghana.