Ghana’s parliament approved the 2022 budget on November 30th, 2021, reversing an earlier rejection by opposition lawmakers after MPs from the majority side staged a walkout. Budget 2022 has been the most contentious in recent history. At the center of the contention is the new 1.75% levy on all electronic transactions including mobile money (Momo) payments. Budget 2022 can be described as bold and ambitious in the quest to slow down debt accumulation and put the debt to GDP ratio on a declining path. In this 3-part essay, I will discuss how the Government of Ghana (GOG) plans to achieve a sustainable debt level by the end of 2025, the realism of the plan and finally, the non-existence of the plan without the controversial e-levy.

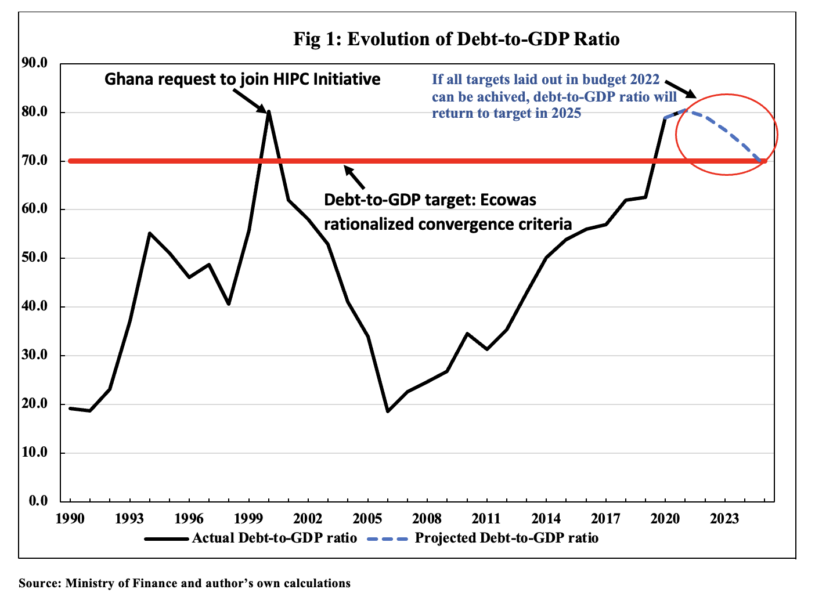

As of September 2021, the accumulated public debt stood at GHS 341.7 billion representing 77.52% of GDP. Given that the government expects to end the year with a deficit of GHS 53.4 billion, the debt to GDP ratio is projected to be 80.4% by the end of 2021[1]. A debt to GDP ratio of 80.4% will be largest on record since 1992, even exceeding pre-HIPC debt levels.

According to the IMF, Ghana first qualified for assistance under the HIPC initiative as early as 1999. However, the NDC government did not think it was in the best interest of the country to pursue debt relief under the initiative. It took a change in government from the NDC to the NPP to pursue the debt relief initiative in 2001 when the debt to GDP ratio was at 80.2%. From Fig 1, it can be observed that the HIPC initiative served Ghana well. The debt to GDP ratio decreased from 80.2% in 2001 to 18.5% in 2006.

With the current debt level exceeding pre-HIPC years, the question on the minds of most economists is “Will the government of Ghana return to the IMF for help?”. The NPP government through the 2022 budget has several ambitious initiatives and targets to return the country’s debt position to sustainable levels. The Ecowas rationalized convergence criteria is a debt to GDP ratio of 70%. This is the target the government seeks to achieve through the medium term (2022-2025) vision and objectives presented in the 2022 budget. According to my analysis and as shown in Fig 1, the debt to GDP ratio, though projected to increase to 80.4% in 2021, is expected to fall to 69.1% by the end of 2025. To achieve that objective the government has set the following medium-term targets:

- Overall Real GDP to grow at an average of 5.6%

- End-December inflation to be within the target band of 8+/- 2%

- Positive primary balance by 2022

- Fiscal deficit of not more than 5% of GDP.

Achieving the above fiscal objectives relies heavily on the medium-term revenue targets. For example, revenue in 2022 is projected to exceed the projected 2021 outturn by 42.9%. The last time the percentage change in revenue was above 40% was in 2011 when Ghana discovered oil in commercial quantities and started collecting oil revenues.

To conclude, Ghana’s debt to GDP ratio will exceed pre-HIPC years. However, in budget 2022, the government presents a plan to return the public debt level to target. In particular, if the government can achieve all its medium-term vision and targets laid out in budget 2022 (including the oil-discovery-like revenue target), public debt will return to a sustainable level without requesting for help from the IMF. How realistic is this? In the next part of this essay, I discuss the realism of budget 2022.

Written by

Dennis Nsafoah

Assistant Professor of Economics

Niagara University, NY

Member of Research Committee, Tesah Capital

[1] Debt at any point in time can be computed as . The 2022 budget puts the public debt as at Q3 of 2021 at GHS 341.7 billion and the expected overall balance for Q4 2021 at GHS -12.6 billion. Assuming there is no other significant flow in Q4. Total public debt will reach GHS 354.3 billion by end of 2021. With a projected end of year nominal GDP of GHS 440.9 billion, the debt to GDP ratio will be 80.4% by the end of 2021.