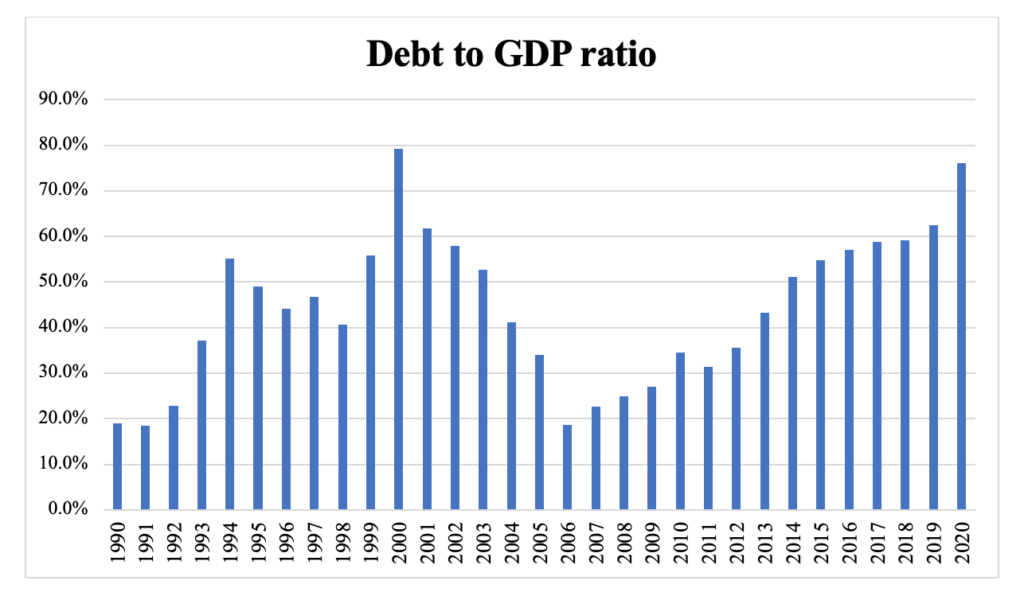

The highlights of the budget presented to parliament on Friday 12th March 2021 were the size of Ghana’s debt to GDP ratio and the introduction of new taxes and levies. The provisional debt stock as at end-December 2020 which stood at nominal figure of GH¢291,614 million, representing 76.1% of GDP is the largest since 2000. The diagram below shows Ghana’s debt level is close to pre-HIPC times. After receiving debt cancelation in 2006 [(IDA and IMF (2006)], successive governments have returned the country to the extreme debt levels in less than 20 years. The government also proposed several taxes and levies to support its revenue mobilisation efforts. See Tesah Capital’s 2021 budget highlights for a summary of the tax proposals. In this article, I will discuss the options available to the government in the light of the looming debt crisis and contextualise the tax proposals made by the government in the 2021 budget.

Source: Author’s calculation based on data from the World Bank and MoF.

In paying the current public debt, the Government of Ghana has four main options available. The government may decide to; (1) issue more debt to pay for the existing principal and interest, (2) announce a default on the debt, (3) monetize the debt by issuing more cedis to inflate away some of the debt and (4) collect more fiscal surpluses (more taxes than they spend). The previous 3 options come with major consequences which make them less desirable or sustainable. As a result, most macroeconomists consider collecting more fiscal surpluses as the sustainable measure for the government to deal with its chronic fiscal deficits.

Issuing More Debt to Pay For the Existing Principal and Interest

When it comes to rolling over debt from one period to the other, the government can only do so much. The government will always have to find creditors who will be willing to lend to them given concerns about the size of its debt stock. These lenders may begin to demand higher interest rates (or cease to lend) especially if the credit rating of the Government of Ghana deteriorates. To be honest, the budget reveals the Government of Ghana currently repays its debt by taking money from the right-hand of investors and handing it back to them on the left-hand. The budget statement shows that interest payment on debt is the largest expenditure accounting for more than a third of all spending. It is fair to say these interest payments are only possible because the government has managed to take on more loans from both domestic and foreign sources. In the light of the recent downgrade from rating agency Moody’s (in April 2020), the government will find it more difficult to attract lenders to make this option sustainable.

Announce a Default on the Debt

Defaulting on the debt comes with dire consequences including being excluded from global financial markets and going through long periods of very strict austerity. Though uncommon, sovereign countries sometimes default on their debt. More recently, Barbados announced the default on its debts after reaching debt level of 175% of GDP in 2018.

Monetize the Debt by Issuing More Cedis

Also, the Bank of Ghana can come to the aid of the government and monetize the debt by printing money to finance it. Just like rolling over the debt, this option is also not a sustainable option because it will generate excessive inflation in the economy. With a CPI inflation rate of 10.3%, which is above the upper band of the inflation target (of 8% +\- 2%), the Bank of Ghana risks runaway inflation should they consider monetizing the fiscal debt.

Collect More Fiscal Surpluses

Finally, the government can start creating fiscal surpluses to finance the debt; a more sustainable means of dealing with the debt. To rationalize the proposal to impose all these new taxes, I get the sense that the government is thinking of dealing with its huge debt by trying to create some fiscal surplus or at least reduce the rate of debt accumulation. There are two main ways the government can create fiscal surpluses – either they increase revenue through taxes or cut spending. One can argue, the government chose more of the former. In as much as I applaud the commitment to dealing with the debt crisis, I am concerned about the specific measures and the timing of these measures.

Where We Go from Here?

As an economist, I admit there are no easy ways to reduce fiscal deficits. However, imposing extra taxes in general in the middle of the worse economic downturn in decades caused by a pandemic may create a lot of disaffection for the government. In particular, some of the measures proposed appear more to me like an afterthought. For example, the government sanitation and pollution levy (SPL) can at best be described as one which needs reconsideration. If the objective of the levy is to improve sanitation and pollution, then a more appropriate tax design should have been one which alters the behaviour of households and firms in relation to sanitation and pollution. This is something I struggle to imagine is achievable with the current 10 pesewas on a litre of gasoil and gasoline.

In conclusion, I would rather have recommended to the government to first consider conducting a thorough examination of its spending to look out for where there are the biggest opportunities for reduction. This would be less likely to generate disaffection for the government and is in line with improving the efficiency of fiscal policy and public financial management as avowed by the government.

Written by:

Dennis Nsafoah